The Bright Side

Alice Peter

For years, there had been nothing but dirt and deafening silence. The kind of silence that makes one's soul shiver to its core. Less silent days, however, were marked with the chanting of angry protestors. "Stop killing our people," they would scream, before they too, were stifled. Then there were blue days with the gossip created when more passed away. "80 killed in Peshawar church bombing and 2 lynched by an enraged mob in Lahore, the entire community should just migrate," they would discuss. Therefore, it almost came as a surprise when, on a sunny morning, sounds of heavy machinery and fierce digging, started echoing in the air. When the nature of the metal structure became evident, the skeletons of thousands of Christians, buried in gora kabiristan, rejoiced in their graves.

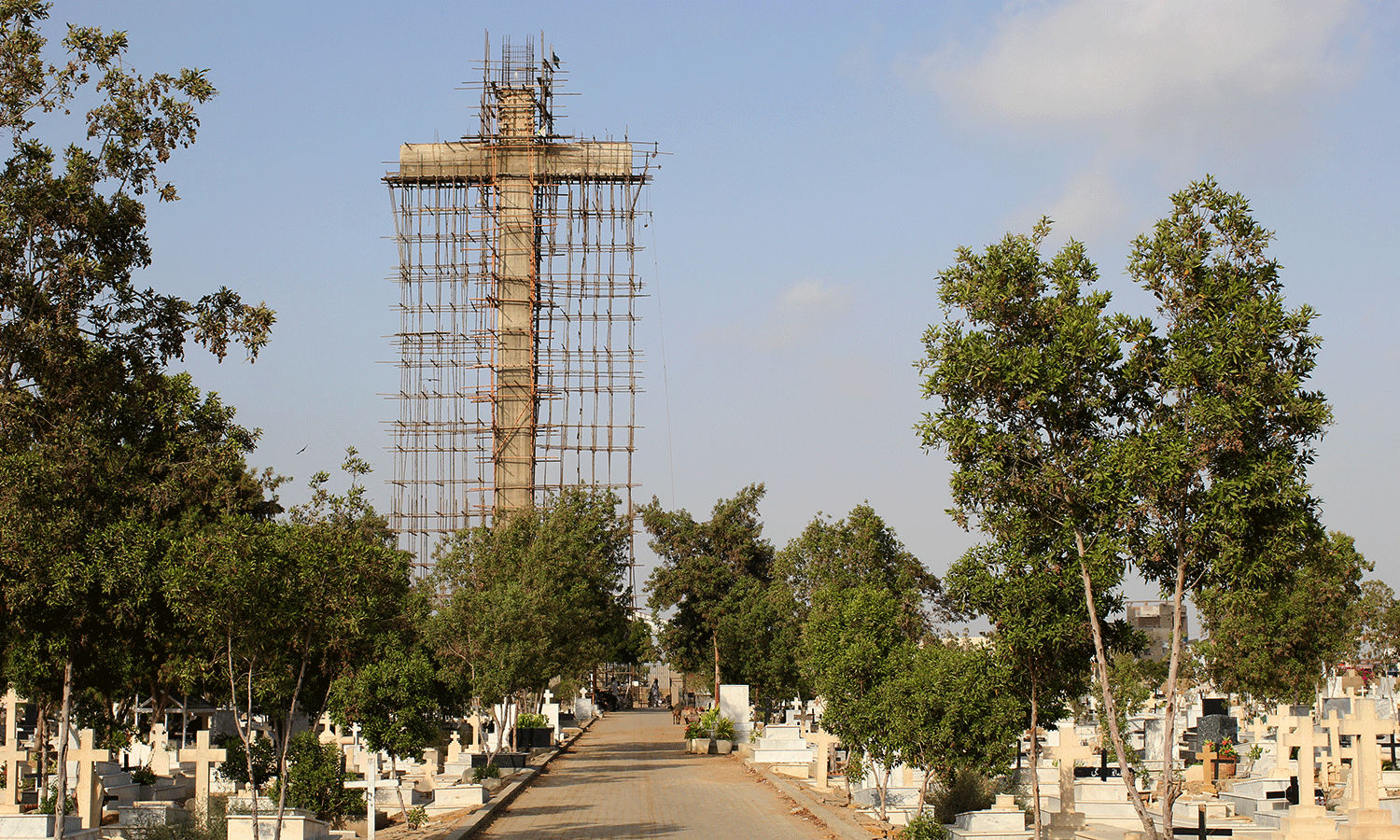

Standing on a 20-feet underground base is the most significant symbol in Christian faith – a cross. And that’s not even the shocking part. Asia’s largest cross, ladies and gentlemen, stands tall and proud at the heart of Karachi: a city known for its many hate crimes on the basis of class, gender, ethnicity, religion, what have you. And yet, this tall structure, visible from afar, is allowed to live on; a privilege that the followers of this faith, on the other hand, do not possess.

Although the building of the 140-feet tall cross is an initiative of a Christian businessman, Parvez Henry Gill, it is rather commendable that he was granted the permission to carry on with his, rather ambitious, plan. For Gill, the message came in the form of a dream where God instructed him to build a cross for his community. And even though he kept his final objective hidden from the construction workers, the minute they discovered what they were building, 20 of them abandoned the project altogether in disapproval.

Ironically, however, Gill’s objective of promoting religious tolerance, by building the cross, included making it bulletproof. Earlier this year, BBC reported Christians constitute 1.6 percent of Pakistan’s total population. This means there are approximately 2.5 million Christians living in Pakistan. We all know how popular the country is when it comes to the ill treatment of its religious minorities in local and international media. Moreover, the already marginalized communities often become targets of terrorism activities in the country. In light of this information, Gill’s decision does not seem entirely baseless.

Nonetheless, how many other countries in Asia, even the so-called secular ones would allow their religious minorities to showcase their faith in a way that is so loud and concrete – literally? Therefore, those of us who despise the very idea of living in Pakistan strictly because of their religious inclination, think again. Denouncing our nation due to flawed ideologies of a few, does not necessarily overshadow the tolerance and desire for religious harmony of several others.

An article that appeared in Dawn on the subject of the cross, deeming it a symbol of hope for Karachi’s citizens, provided information on one worker’s decision to stay back and continue construction. Although 20 of his fellow workers quit building the cross, Mohammad Ali, called the project a “work of God,” and therefore is still a part of it. Now a pessimist who has made up his mind about leaving Pakistan and wishes to seek asylum in some other part the world, may consider this information ‘rare’ or an ‘anomaly.’ But realistically speaking, Pakistani Christians are children of the soil and if one out 10 siblings wants us to stay, then we stay.