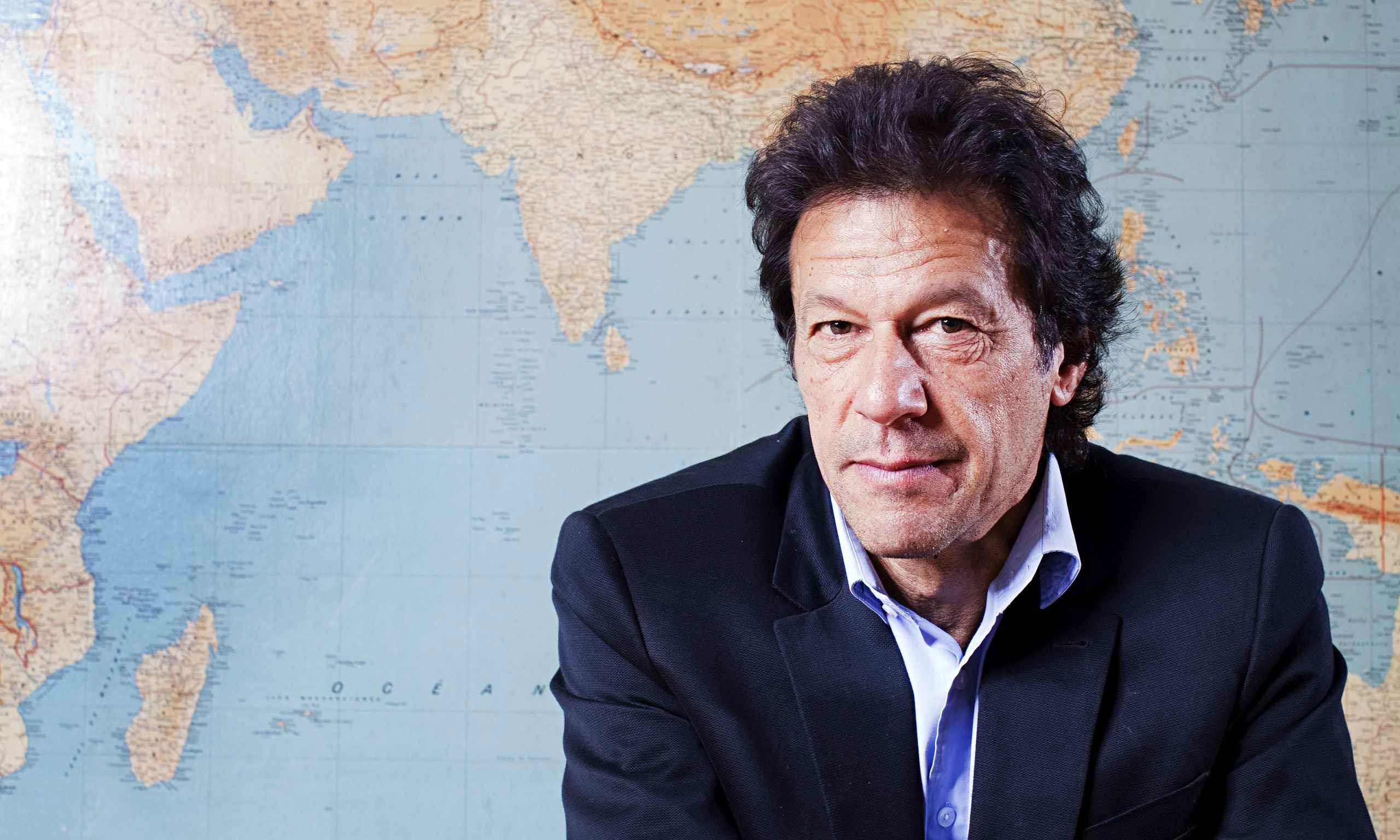

Who Is Imran Khan Anyway?

Understanding the enigmatic

Frayan Doctor

Three years can be a very short period of time in different fields of life, but in politics, three years can be the difference between heading a nation’s executive or being cast into the wilderness forever.

While Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI) Chairman Imran Khan’s – the 63-year-old cricketer turned politician – political fortunes have not nosedived, he and his party are no longer enjoying the explosive wave of popularity that they did 12 months prior, and up to, the general elections in March 2013.

Khan has always been an enigmatic and charismatic figure. From his days as an Oxford University student – slain former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto was studying there at the same time – to leading Pakistan to its only cricket World Cup victory in 1992, the son of a wealthy businessman has always been a divisive figure amongst his legion of supporters and fierce critics.

His brash and confronting style as captain of the cricket team created deep schisms between the players that supported him and those, along with the management, that opposed his leadership. His playboy and womanizing lifestyle generated tabloid frenzy in Britain as a cricketer. His critics in Pakistan were equally scathing of his morals, values and behavior, which go against the ethos of a deeply religious and conservative Pakistan.

Age has not prevented him from mellowing his rhetoric. He vehemently opposed retired Army General Pervez Musharraf’s dictatorial rule. His vocal criticism of dynastic politics and the two-party civilian rule of the country and outspoken opprobrium of America’s military campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq and its drone campaign in Pakistan’s tribal areas can all be traced back to his flamboyant days as one of cricket’s greatest all-rounders.

For the young Pakistani generation – over 60% of the population is below age 25 – Khan emerged as the new and only untried and untested alternative to Asif Ali Zardari, Nawaz Sharif and the old stalwarts of Pakistan Peoples Party and Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz. But, his obsession with electoral rigging and energy-sapping political rallies and dharnas has meant that he has not devoted his efforts to governing Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) effectively.

He will never lose the support from his core Electoral College of young urban and rural elders of the northern and tribal areas based on his alternate political appeal cricketing exploits. The affluent that have been disillusioned by dynastic politics and willing to financially support PTI see something of themselves in Khan, i.e. devoutly Muslim, proudly nationalist and successful. However, his lack of political experience, sound strategy and political whitepaper mean that support for him will only last for so long. KPK is the biggest examination of his political career to date.

And if he is to be as successful in this game as he was in cricket, he needs to unite his diverse constituencies of urban, middle-class Pakistanis and the deeply conservative people in the tribal areas. He ought to win over the hearts and minds of Sindhis and Punjabis to effectively transform his fortunes and bring his party to the forefront of Pakistani politics.

Understanding Khan’s Leadership

Hina Javed

It is said that a successful leader has style, optimism, and leads by example. While Imran Khan may have outdone his politics based on his style and charisma, he has regrettably displayed a questionable stage show in the other two areas. The cricket superstar turned politician is ambitious, power-seeking, and impulsive, but is pre-occupied with his rallying cry of ‘Tsunami araha hai.’ The impact of this has already been witnessed in Kyber Pakhtunwa. Khan has made more noise and displayed little.

In his politics, Khan has been the bigger force than the party itself. A cricket hero, who brought the World Cup to a nation starving for pride and recognition, a man compensating for the dearth of good looking politicians in the country, a selfless and trustworthy philanthropist, and a politician with a clean history and power to uplift spirits, is now lauded by the country’s middle class and revered as their charismatic leader. Most of his young fans are cricket enthusiasts and base his future performance on his sporting success and philanthropic work. For them, being an honest man is all that is needed of Khan to turn Pakistan around and win him ambiguous populism. But here, I’d like to bring to attention the fact that leading a nation as opposed to captaining an 11-member cricket team, are two absolutely different phenomena’s. Even though Khan has great potential to lead and inspire the nation, most of the party members left Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf, not because of party politics, but due to differences with Imran Khan. Most people in politics conveniently blame him for being arrogant and inflexible. And when it comes to national and international issues, Khan is even more adamant in his stance. The young man of Pashtun blood wanted to end Pakistan’s slavery to America, but was ever ready to negotiate with terrorists, something the entire nation stood against. Furthermore, Khan’s political strategy was simple. He promised to uproot corruption within 90 days, end America’s war on terror and constitute an Islamic welfare state. But in his quest for a moral Pakistani state, he failed to revisit his own youthful journey. In his autobiography “Pakistan: A Personal History,” Khan effectively dismisses his many un-Islamic deportments. References and chants of Allah and Islam increased as he struggled to break into Pakistani politics. His acknowledgement of Islam, identification with the underprivileged class, and attacks on the affluent has often been mocked by the people who also call him “Taliban Khan”. Nevertheless, Khan’s autobiography gives a compelling picture of a person with clashing identities.

Imran Khan essentially intrigued those sections of the middle class who have been apolitical all their lives and had given up on the overall state of affairs. Most importantly, Khan attracted the unhappy educated youth who had no clear direction and saw no future in Pakistan. On the other hand, if one were to analyze the attention he got from the urbanized women, then it’s fair to conclude that Khan enjoyed the popularity of a fanning celebrity. Imran Khan’s politics represent a conservative mindset that questions democracy and believes in miracles of change. It is authoritarian despite its liberal appearance.

Confusion All Around An All-Rounder

Alice peter

The privileged youth of Pakistan is often stereotyped as being jacks-of-all-trades, and yet masters of none. With photographers aiming to be filmmakers, doctors and engineers gearing towards becoming TV hosts, and politicians aspiring to be clerics, diversity has become the easy path to noteworthiness. And while some must do everything to enhance their skillset, others just happen to be born with the golden touch.

Such was the luck of Imran Khan Niazi – a golden boy of Saraiki/Pashtun1 background, born to an affluent2, Anglicized-Pakistani household and raised to be rather “Westoxified” – of course, he would grow up to center his politics on the downfall of these “English-speaking, upper class types” such as himself, but that is a different topic altogether.3 What is undeniable, however, is his ability to be exceptional at whatever he does. Unfortunately, for him, it never proves enough; and sadly, for the rest of the world, what a sheer waste of talent.

Let’s backtrack a little. It is 1971. A 19-year old boy makes his international cricket debut in a test match. 4 He does not make much of an impression but is far from disillusioned. Not only does he return to international cricket, a few years later, but he also brings with him the will to take the game by storm.5 What happens next is common public knowledge. The initially sidelined young boy, Khan, goes on to acquire the team’s captaincy and showcases some of the best-played matches the country has seen. Having reached the pinnacle of his career with Pakistan’s sole World-Cup victory, however, he decides he has had enough of it.

Khan’s acumen for cricketing strategies and his willingness to physically challenge the improbable may as well have made him the first Pakistani to be titled ‘sir,’ who knows? But despite realizing he may be robbing the world of an extraordinary sports analyst, he still chose to retire. His unwavering detachment from cricket, a sport that served a huge part of who he was, reflected his rich-kid-syndrome, one he still hasn’t recovered from. As if international cricket were a toy he wanted, so he cried and threw a tantrum till he got it. But once achieved, the toy lost its charm forever. Amidst Khan’s philandering days, which gave rise to the infamous ‘Im The Dim’ phenomenon6, his mother was diagnosed with cancer. Her death in 1985 acted as primary motivation for the Shaukhat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital in Lahore.7 Onlookers may have anticipated the inauguration of this facility as Khan’s official commitment to social work in the health sector. However, for Khan, his contribution was pretty much done.

With his determination and source of inspiration, he could have easily dedicated all his time and effort to the expansion of Shaukat Khanum, taking the organization to heights where its name would become synonymous with cancer in Pakistan. But Khan already had one hand deep into politics; hence his confusion, to be Edhi or to be Bhutto? Here’s a better plan: abandon philanthropy altogether.

The dawn of democracy in Pakistan made Khan the second most popular politician of the country, after Benazir Bhutto.8 Only difference: his followers sit behind their expensive laptop screens and “tweet” in his support. Khan makes an impression once again, but somewhere along the way, he loses his enthusiasm. So far in his political career, he is conflicted; whether he is the leader of the educated elite or the representative voice of the common man, he cannot decide.

See you can’t do both, because these two groups have an ongoing class conflict since time immemorial – study Karl Marx if you don’t believe me. Fighting for the rights of the poor by mostly shaming the class he himself reeks of, has made Khan a modern- day political paradox. His starched shalwar kameez, partridge hunting hobbies9 and moody career objectives make him a quintessential case of confused identity; the likes of whom take pride in introducing themselves as ‘spiritual’ as opposed to ‘religious,’ because it’s cooler.